SOIL TEMPERATURES IMPORTANT FOR SEED GERMINATION

In early spring excited gardeners like talking about the "growing season" characterizing it as being wet, dry, cold, warm, early, late, etc. But what exactly is a "growing season"? A "growing season" is commonly recognized as the average dates between the last frost of spring and the first frost of autumn delineating the span of time plants have to complete their annual growing cycles.

In most of Rensselaer County, the historical growing season covers about 150 days. Recent data from the US Environmental Protection Agency shows that New York's growing season since 1970 has increased to around 160+ days. This means that our favorite vegetables have ample time to sprout, grow and be harvested because most of these vegetables complete their growing cycles within just 85 to 120 days. The downside is that the longer season reflects the effects of global warming that also may bring more extreme weather events such as heavier rainfalls, higher temperatures in summer, and the arrival of new pests from southern climes -- things that vegetables don't like.

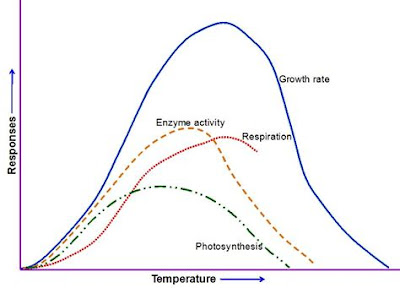

Home gardeners, however, need to focus on more than just that last frost in order to get a head start on either spring or their neighbors. Some other important factors affecting a given year's "growing season" include air and soil temperatures, rainfall patterns and soil moisture as well as light levels to name a few. Of these, air temperature is arguably the most critical factor as it provides the energy (i.e. heat) that determines a plant's germination and growth rates.

Cool weather vegetables such as peas, spinach and radishes will start to germinate in soil temperatures around 40°F, while warmer weather crops such as bush beans, cucumbers and squashes germinate at soil temperatures starting at around 60°F. The two charts below clearly illustrate these differences in seed germination requirements.

For both peas and bush beans, optimal seed germination occurs at distinctly warmer soil temperatures than threshold temperatures, germination rates increase up to a peak soil temperature and then decline eventually ceasing as soil temperatures exceed the optimum point. Seeds planted at or near their peak germination temperatures sprout faster and may emerge within only a few days. Seeds planted at threshold gemination temperatures will take longer (e.g. a couple of weeks or more) to germinate and emerge because their chemical activities, although triggered, are occurring at much slower rates. This means that it may not be advantageous to put seeds in the ground at the earliest possible time if air temperatures are forecast to remain around germination threshold levels.

Cool weather vegetables such as peas, spinach and radishes will start to germinate in soil temperatures around 40°F, while warmer weather crops such as bush beans, cucumbers and squashes germinate at soil temperatures starting at around 60°F. The two charts below clearly illustrate these differences in seed germination requirements.

|

| Sugar snap pea. Source: Johnny Select Seeds |

|

| Bush bean. Source: Johnny Select Seed |

For both peas and bush beans, optimal seed germination occurs at distinctly warmer soil temperatures than threshold temperatures, germination rates increase up to a peak soil temperature and then decline eventually ceasing as soil temperatures exceed the optimum point. Seeds planted at or near their peak germination temperatures sprout faster and may emerge within only a few days. Seeds planted at threshold gemination temperatures will take longer (e.g. a couple of weeks or more) to germinate and emerge because their chemical activities, although triggered, are occurring at much slower rates. This means that it may not be advantageous to put seeds in the ground at the earliest possible time if air temperatures are forecast to remain around germination threshold levels.

Home gardeners also need to note that seeds of different vegetables respond differently to soil temperatures that are too cool or too warm for germination. Radish and parsnip seeds can be planted in soils below their threshold germination temperatures. They will just sit and wait until soils warm up. Bush bean seeds planted in soils below their germination threshold run a high risk of never sprouting and just rotting as their seed casings soften from soil moisture. In summer, high soil temperatures near the surface will cause some plant seeds, e.g. many lettuce varieties, to go into a dormant state.

Measuring Soil Temperature

I use a metal bulb soil thermometer to check soil temperatures in spring before planting seeds or setting out seedlings. You can also use typical household thermometers as long as their scale goes down at least to 32°F, but you may have to use a screwdriver or small trowel to soften the soil before inserting those plastic models into the ground. I measure soil temperature at a depth of 6." Soil temperatures will be warmer, of course, closer to the surface which will be better for seeds, but I am looking for temperatures that roots will like after the seeds have sprouted.

|

| Metal bulb soil thermometer |